By Pinky C. Serafica

“Siddharta, The Musical,” is the kind of art piece that finds. It is easy to go eye-level and be sated by the visual feast or breeze through an afternoon of the biography of an icon who shaped a major religion.

It is harder to sift through the tensions and dissonance in the play unless it is where the viewer has a front seat of her own swordplay-within. Or be conscious of the unending cycle of questioning, seeking, resolving temporarily, and knowing that as long as we are alive, the sequence repeats.

An original production by Chu Un Temple that had many reruns since 2007, this version of “Siddharta, The Musical,” as explained in the introduction by a narrator, was directed under the Fo Guang Shan Academy of Art, and adapted for schools.

The play sings and dances the life of Prince Siddharta, the beloved and protected son of a powerful monarch who was intent on molding an heir to preserve and even expand the kingdom. Despite carefully curating the environment around the prince, the real world still catches up with Siddharta which triggered the legendary journey to find truths.

In every turn of the play, the repeating threads are sung—of internal dissonance, and then the truths-seeking, the understanding and self-discovery, and because we are human and prone to cycles, the threads repeat from the in-betweens of birth to death.

The musical opens with a rousing number of Indian-Filipino movement and rhythm, setting the scene to the first dissonance. Although powerful and leading a wealthy kingdom, King Suddhodana is desperate, and sings of the longing— “this kingdom needs an heir”—to have a son to continue the dynasty. When Queen Maya gives birth to the boy, Siddhartha, a seer prophesied that the prince would either follow after the father or become a great spiritual teacher.

The celebrations that welcome the birth of an awaited child is accompanied by the tension of performances—each person in the immediate surroundings of the prince is ordered to act roles, carefully curating a life free from suffering—what Siddharta sees, smells, tastes and remembers are manufactured and designed to present a superficial world to make him stay.

Although untold in the play, his parents’ and the palace’s staff must have doubled their own dissonance, painting a fine life for the prince, and then going back home to face what they all hid. As foil to King Suddhodana’s strong singing presence and robust dancing behind him to ward off his internal conflict, Queen Maya sings quieter, upending her own truth-seeking to realize: “My Son is Not My Own.” The song is sourced from Kahlil Gibran’s poetry of acceptance that children are “the sons and daughters of life longing for its own,” they may be with us, come through us but do not belong to us.

But the real world can not be kept at bay for too long when Prince Siddhartha eventually sees someone sick and aged—he was an infant when his Queen mother dies—and begins his questioning only to be told that sickness and aging will lead to inevitable death. To distract him from a path of seeking, King Suddhodana curates love, and the prince is wed to Princess Yasodhara in yet another grand party.

Having felt the contradiction though, no marital happiness, safety and material consolation could mask his conflict, and the prince decides to leave the protection of the castle, and blaze a path leaving his bride and a powerful parent behind. From the multi-layered rhythm and movement in the first half of the musical, the play quiets down to spotlight the prince’s truths-seeking.

Siddharta, now with the eyes of a commoner finds sightings common to non-princes: an old person aging; a sick villager debilitated; a corpse and inevitability; and a holy person looking to seek and understand truths. Five attendants dispatched by the king to bring him back do the opposite and instead steps on his path, but find the man in the seeker, not yet the spiritual icon that they thought him to be.

Two striking scenes highlight the internal-external conflicts experienced by seekers and their followers who tend to pit them against stiffer standards or isolate them on pedestals. The five attendants see Siddharta pause from his meditation and austerity to drink goat’s milk triggering many whys that are still being asked today: should seekers isolate themselves and practice self-denial to prevent temptations? Can enlightenment be balanced with satisfying bodily nourishment? How can seekers lead a spiritual life while still deeply involved in community affairs?

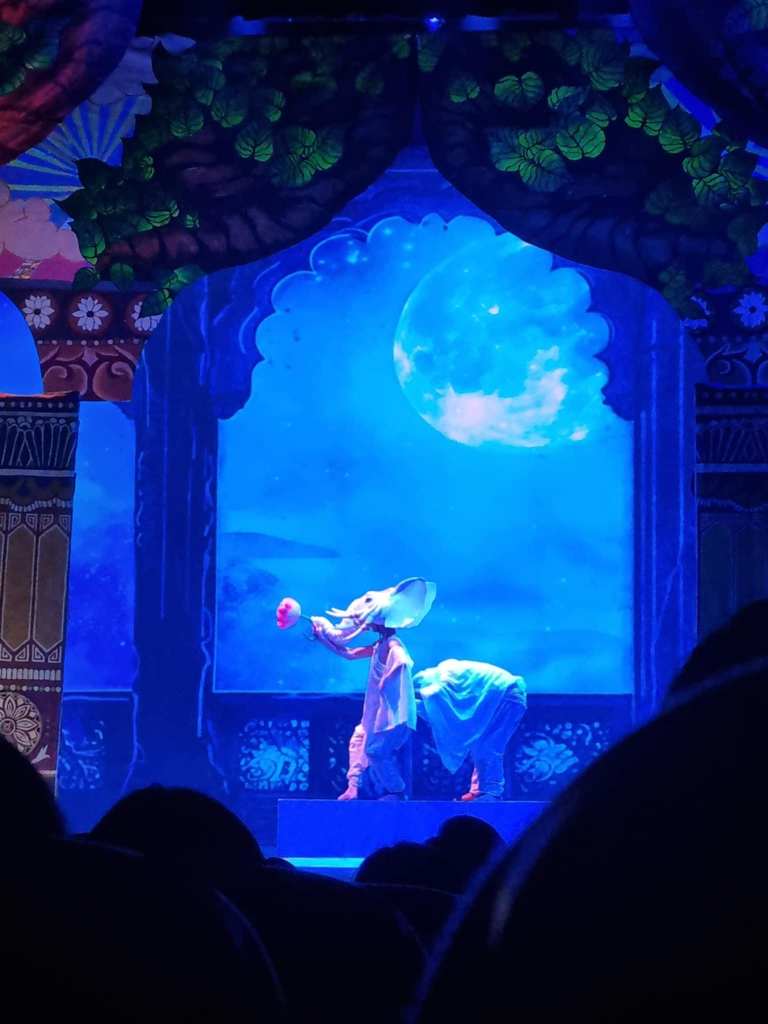

A “mara,” an entity in Buddhism that hinders awakening, then tempts Siddharta with daughter-spirits of greed, fear, ignorance and desire . Siddharta remains in meditation, acknowledging the pulls of his ego, and how his reaction could fuel more internal provocations and attachments in an endless cycle. The raucous segments end with a striking character in pure white with a horned creature posing against a stark blue background as witness to Siddharta’s enlightenment.

Siddharta becomes Buddha espousing a “middle way,” balancing spiritual practices with nourishment and building strength, living in communities with compassion for other beings in their own paths. He walks this path returning to a warm reception from father and spouse, both expecting a son and a husband back only to find a changed teacher challenging their old ways of living.

The musical could have ended here for more philosophical and theatrical impact. Perhaps because it was meant for schools, the creative team opted to extend the play some more to showcase the effects of the Buddha’s way to others outside of his familial circle.

But because “Siddharta, The Musical,” is the kind of art piece that finds, viewers’ wayfinding is scattered throughout the play—whether they are on a spiritual path or simply just enjoying a musical—taking on the dissonance, truths-seeking and self-discovery in whatever way as long as it works. WWW