By Diana G. Mendoza

For 10 years as a barangay health worker (BHW), Pilita Alcantara is more than gratified to know that she has helped so many people and she realized that the lives of some of these persons often mirrored her own.

One of those instances occurred when her 15-year-old son got a 16-year-old girl pregnant, which, to her whose responsibilities include advising young people to be sexually responsible and not rush into relationships, was both tragic and ironic.

“Lagi ka kasing wala. (You’re always out),” Alcantara’s son told her when she asked him where she might have been remiss as a mother. “Ang sakit sa akin nun (That hit hard),” she teared up during an interview. “Andami kong natulungan pero sarili kong anak hindi ko napagsabihan (I helped many people but I forgot to give advice to my own son).”

The sadder part was when the teen girl’s mother called her up to tell the bad news, it was already a month before the girl was about to give birth, which means the pregnancy was kept from her. “Overnight, I became a grandmother and my son became a batang-ama (young father),” she said.

Her grandchild, who calls her “mommy,” is now a six-year-old boy and is under her care, a role that she is happy to do, along with caring for her husband, son and a younger daughter. The teen parents have separated, but Alcantara maintains a good relationship with the girl’s mother, for the sake of the boy’s parents who are now young adults and for their child who was borne from an unintended pregnancy.

Hard lessons, new roles

Alcantara moved on and shifted roles from a BHW in Barangay Imelda Marcos (La Salle) in Baguio City, to a barangay kagawad (also konsehal or councilor), after she ran for the post in the October 2023 Barangay and Sangguniang Kabataan (SK or youth council) elections and won.

Her schedule now requires her to be on barangay duty every Monday and to participate in the council meetings of every month’s first and third Thursday. She is also in the committees on sanitation, environment and tourism.

For her new role, Alcantara brought along the hard lessons from her pains as a mother and difficulties as the primary caregiver of her family while assisting people in her barangay, which often entailed an almost 24-hour service, out-of-pocket expenses and, during the pandemic, being infected with Covid-19 twice.

“Sometimes I come home late due to the work load. I also have many calls even while at home. That’s why my son always chastised me for being able to clean up the barangay but neglecting our home,” she said. But she will always cherish the appreciation and respect of the people she helped as a BHW – fond thoughts that she will always remember now that she is in a political post.

The Local Government Code of the Philippines describes a barangay councilor or kagawad as an elected government official who is a member of the Barangay Council that serves as the legislature of the barangay, the smallest political unit in the Philippines, and is headed by the barangay captain. Councilors are elected to three-year terms, with a term limit of three consecutive years. There are seven councilors per barangay. The barangay captain, council members and peacekeeping officers are considered persons in authority in their communities.

From volunteers and to leaders

For Alcantara, running for a public post was “a huge step from being a volunteer who is called 24/7 to assist people to that of a leader who is now part of decision-making.”

In Alcantara’s barangay, the captain is also a former health worker – Lucia Dolteo, a former barangay nutrition action officer (BNAO), who has received recognition as the best BNAO for five years.

She ran as village chief unopposed in 2023, but before that, she has been a councilor for nine years. As kagawad during the pandemic, she worked with BHWs and local social welfare department workers in doing house-to-house interviews to know how people are doing and in distributing food packs.

As barangay captain, Dolteo’s functions are broader now than when she was a health worker. “My function is to lead, delegate and see to it that kagawads do their responsibilities.” She leads the monthly community assembly where they meet with residents and discuss pressing concerns. She said there are challenges, “but if you love your work, people become receptive and are able to participate.”

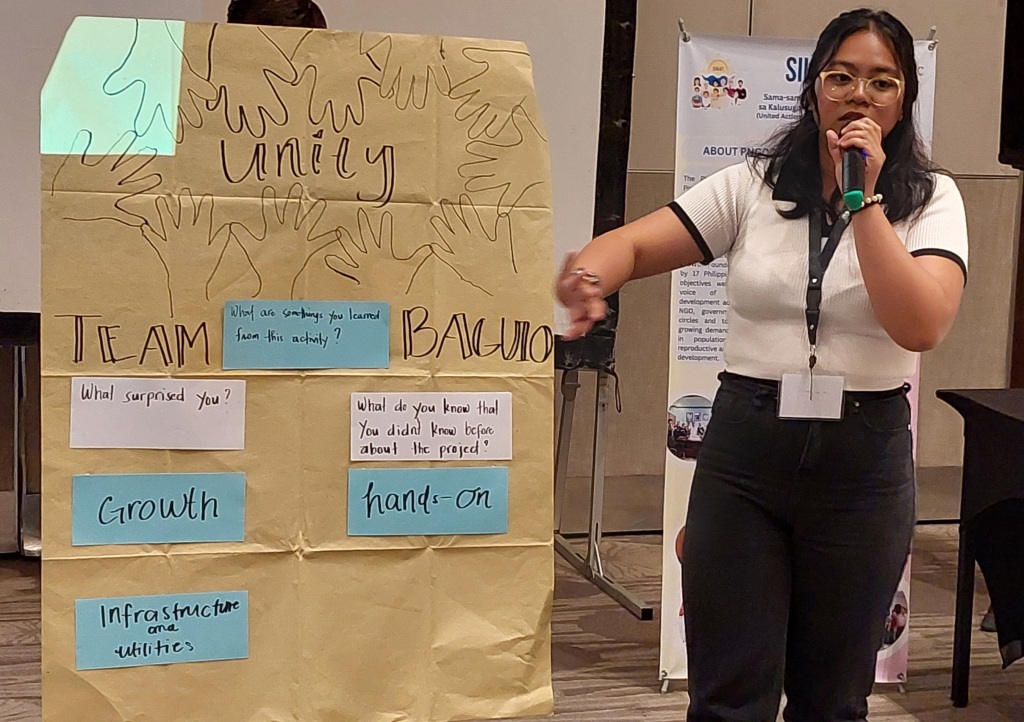

Alcantara and Dolteo were part of the Philippine NGO Council on Population, Health, and Welfare, Inc. (PNGOC)’s SIKAT project or Sama-samang Inisyatiba para sa Kalusugan ng Taong Bayan sa Universal Health Care that was piloted in Baguio City and two other localities. The project was about to conclude when they were interviewed. They also provided their assessments of the project that aimed to contribute to reducing data gaps on primary health indicators through a baseline data on the city’s health situation.

“Any efforts either by the local government or organizations such as PNGOC to help us improve the health-seeking behavior of people is always welcome,” said Dolteo. “We just hope activities like these are sustained.”

Chi Laigo Vallido, PNGOC executive director, said, “the ranks of BHWs have always been the lifeblood of the SIKAT project and future projects that help reinforce the pathways to community health care.” She said this factor contributed to the project’s success and in continuing initiatives such as strengthening routine vaccination to improve health.

Youth gaps

Youth leader Cathrina Mae Carbonel, SK chairperson of the Saint Escolastica Village, Baguio City, filled in the post that has been vacant for 10 years “because no one wanted to lead.” Carbonel said the main concern in her barangay is adolescent reproductive health – “there’s a worrying number of teen pregnancies” — and youth mental health.

The graduating political science student of the University of the Cordilleras said “there is lack of knowledge about reproductive health and the young people don’t know who to ask for help and where to ask questions.”

Bullying is prevalent. “There’s one youth who stopped schooling and doesn’t want to go back because of bullying,” she lamented. Her plan now is to be able to fill in the information gaps and connect the youth to the health services that they need. “I made a resolution to the barangay that I make a social media page so that we can communicate with the youth,” she said. “When I was a teenager, I didn’t realize that we can have screening and checkup and we can ask for information materials. I plan to connect the youth to such services.” WWW